Two years ago, while taking the last class of a live online course for folks managing life with ME/CFS, I noticed in the chat box that one of the course assistants who was also living with the illness had announced that she had a few openings in her private therapy practice for anyone looking for added support. Having been on a months-long, exhaustive search for a therapist who specialized in treating folks with chronic illness, I’m certain I emailed her while the class was still in session.

Jamie turned out to be a home run of a therapist and I fan-girled pretty hard in the beginning on all the things we had in common. She was also partnered to a man, had no children, and had a sweet older pup (okay, we have cats – but we sometimes refer to them as puppies🐈⬛🐶). One of our diagnoses (ME/CFS) overlapped, and importantly, she had learned how to pace her way to significant recovery – a skill I was very eager to learn from her, as I wanted life as I knew it in the “before times” to come back, stat (Ha! Yeah right. Stay tuned for that post).

In the early weeks as we were getting to know each other, she quickly learned about my tendency to use humor as a defense mechanism (I’m nothing if not exceedingly therapized and self-aware). Unlike some of my previous therapists, she wasn’t hell-bent on slowly ripping this particular self-preservation tool from my cold, pale hands. Instead, Jamie glided along its current, laughing at most of my jokes (did I mention she’s Canadian?) while still finding openings to skillfully and tenderly push me on my shit.

In the beginning, Jamie was being what every therapist (or counsellor, in Canadian) worth their salt strives to be – boundaried (yes, I’m verbing where I shouldn’t be – and verbing is actually a word). At the same time, she was great at sharing bite-sized details about her life here and there. As a social worker myself, I have a lot of respect for therapists with good boundaries who know how to slowly open the valve of personal information just enough to build a genuine, human relationship with their clients.

On the other hand, as an uber-curious evil little shit, I routinely set such respect aside and needle right past the boundaries of any professionals with whom I interact regularly (I have a real immature need to become the favorite patient in doctors’ and dentists’ offices – give me ALL the attention! But don’t realize you’re doing it because you genuinely like me. Can you see why I’m still in therapy?).

And so it was that over time, I used my extrovert wiles to draw Jamie’s own wicked sense of humor to the surface. Baldy (my long-standing nickname for the best husband ever, whose main distinguishing physical characteristics are the cutest dimples ever AND a beautifully shaped dome, IMHO) would sometimes comment upon my emerging from a therapy session, “there was a lot of laughing going on in there.” Indeed there was, but there was also crying, learning, and growing, and that’s why Jamie was so great. I could be who I was and still get the ass-kicking I was paying for.

Pacing (or, I promise I’m getting to the underwear part…)

The single biggest thing that Jamie and I worked on for two full years was the concept of pacing, an energy management tool that can be very helpful to folks living with Long COVID and ME/CFS, if done effectively.

Some important definitions:

“Pacing is an active self-management strategy whereby individuals learn to balance time spent on activity and rest for the purpose of achieving increased function and participation in meaningful activities.” [1]

Pacing recognizes research showing an abnormal metabolic and immunological response to exercise in ME/CFS (and in some with Long COVID) and offers patients a middle ground between post-exertional malaise (PEM) and the negative consequences of inactivity. PEM is a worsening of symptoms or the emergence of new symptoms after physical or cognitive exertion, most often delayed by 24-72 hours and possibly lasting for days, weeks, or months. PEM is considered the hallmark symptom of ME/CFS and makes living a “normal,” active life extremely challenging or impossible.[2]

As you may well imagine, pacing, though necessary for achieving any kind of quality of life with these illnesses, is extremely difficult for those of us who have always been moving, doing, achieving. After all, what is life about if we can’t do the things we’ve always done to bring us satisfaction? (Notice I didn’t say happiness; again, stay tuned for that future post). For me, those things were working in a career I loved, at a job I loved, and being very physically active: hiking, volleyball, cardio, weightlifting, learning tennis. I also loved going out, being social, laughing a lot and making other people laugh.

Jamie cracked the code on pacing relatively early after the onset of her ME/CFS. She basically “went under” for a full year; she stopped working, stopped seeing friends, stopped driving, and spent her days resting, meditating, and sitting out in nature. Admittedly, this type of hard-core attempt at recovery is for the privileged. Jamie has a loving partner who became the sole earner in the household and who also picked up virtually all of the cleaning and chores. They invested a lot of their fast-dwindling resources in her recovery (she has a home oxygen chamber, for example, since people with ME/CFS and Long COVID are known to not get enough oxygenated blood to their vital organs) and they made a lot of difficult but necessary decisions about their way of life, moving into a smaller condo and becoming a one-car household.

It worked. Jamie slowly emerged from the worst of her ME/CFS and was eventually able to open her private counselling practice. She only saw a few clients a week in the beginning, later ramping up to about four sessions a day with generous time breaks built in between so she could continue resting and pacing. Sure, she had some crashes, but she also knew how to pace her way out of them in time.

I wanted so badly to soak up what Jamie had, this mystical quality of being able to put productivity and to-do lists aside and just BE.

But, as Jamie frequently pointed out, fully integrating these lessons was HARD and would take time. It meant changing 45 years of my wiring and becoming this easy-breezy, water off a duck’s back type of person. I would have a day or two of what I thought was progress, feel a tiny bit less fatigued on day three, and decide to clean my entire kitchen, top to bottom. CRASH. Back to square one.

This cycle happened to me probably hundreds of times in the two years I worked with Jamie. Even after I stopped working and was on full-time disability leave, I found it hard to ignore my household to-do list and to “indulge” in resting. Jamie insisted I was still learning and that even baby steps were progress. She also gently unraveled the twisted, knotted yarn ball of my psyche that somehow made me feel like rest was a dirty word and that I was undeserving of rest without having accomplished at least one task first.

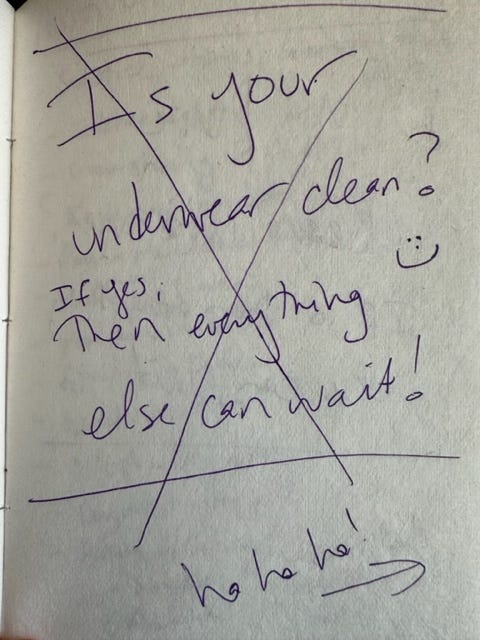

It was during one of our typical sessions that she said something to me like, “you have to learn to live with a dirty house…to shrug off the dust in the corner. Just ask yourself “Do I have clean underwear?” If the answer is yes, then everything else can wait.”

I laughed and then she laughed. It felt like brilliant advice to me, practical with a side of funny. I kept a therapy journal during my time with Jamie so that I could reflect on things she said or revelations I may have had after our sessions ended. But I sometimes forgot to write down her gems until after the session, and so it went with underwear day. Here is what I first wrote:

It wasn’t until a few days later that I realized I had gotten her question wrong in a most hilarious way. She didn’t mean “is the underwear you have on now clean?” (though not an unimportant question!). She meant “do you have some small stockpile of clean underwear, enough to allow you a string of days to rest and still be hygienic?” I crossed out the first journal entry and corrected it on the following page:

At our next session, when I told her about my gaffe and showed her these journal pages, we laughed even harder than we did when she first said it. I’m sure Baldy was overhearing the laughter thinking “what the hell are we paying for – an improv class or therapy?!”

Jamie is now on maternity leave for a year, her seemingly against the odds pregnancy a fact that both inspired me (wow, look at her crushing it at life amid this illness!) and selfishly devastated me (what would I do without her?!).

And then something amazing happened, seemingly out of nowhere, as these moments of real progress often do when you’re working with a great therapist. A month or two ago, just before her leave, pacing just sort of…clicked into place for me.

I can’t pinpoint exactly what it was that caused this to occur, other than the combination of Jamie’s tender persistence around the subject and ME/CFS recovery books and videos I had been consuming. Medications, supplements, diet, massage, acupuncture, red light therapy, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, you name it – while these may have aided recovery for some, their efficacy was somewhat random and specific to the individual. All who meaningfully recovered their health, however, incorporated some level of pacing into their lives.

I am now paying much more attention to my activities. I am resting and meditating periodically throughout each day and listening to my body as fatigue starts setting in during a task. I am still hoping to get better at stopping my activity just before feeling that fatigue. More and more, I am saying no to events and requests that will drain me.

Jamie would be happy to know that I have a full drawer of clean underwear. I am ready.

Post-script

This post took me several days to write, in 20-30 minute blocks of time. Putting the finishing touches on it yesterday + bending over repeatedly for three minutes to clean a dirty cabinet, which sends my heart rate shooting up to 120 beat per minute as if I’m jogging = PEM for me today, 24 hours later. Fatigue and shortness of breath are both amped up; neuropathy will come later today.

Pacing lesson: write shorter posts. You as the reader may appreciate that anyway 🥱.

If you’d like to learn more about the specific brand of fatigue that comes with Long COVID and ME/CFS (it is NOTHING like the tiredness that comes with everyday life), check out this recent article in The Atlantic by the brilliant Ed Yong. He also wrote the first article I ever read about this mysterious thing called Long COVID in June 2020, sending me to all the online support groups and kicking off my medical self-advocacy summer tour (just picture the tour t-shirts ✌️😎🎶) that turned into a three-year, Elton John-esque goodbye tour.

If you like what you’ve just read, please share and/or subscribe. Subscriptions are free (for now, until I can figure out a way for the disability insurer to keep their grubby paws off of any money I earn).

[1] Jamieson-Lega, Kathryn; Berry, Robyn; Brown, Cary A (2013). "Pacing: A concept analysis of a chronic pain intervention". Pain Research & Management : The Journal of the Canadian Pain Society. 18 (4): 207–213. ISSN 1203-6765. PMC 3812193. PMID 23717825.

[2] https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Post-exertional_malaise, accessed on 7/26/23.

I love this post! So reflective and full of humour. It reminded me that in the middle of a crash last year I had to order new underwear on Amazon when my washing had piled up. I remember thinking old me would beat myself up for not putting on a wash, but new me knows how to stick to my baseline.

As my mama says, “Always wear clean underwear. You never know.” So a small stock sounds right 👌🏼